elemintalshop

Chinthe Leogryph (Lion) & Burmese Lacquerware Artisan 50 Kyats Myanmar Authentic Banknote Money for Jewelry and Collage

Chinthe Leogryph (Lion) & Burmese Lacquerware Artisan 50 Kyats Myanmar Authentic Banknote Money for Jewelry and Collage

Couldn't load pickup availability

Chinthe Leogryph (Lion) & Burmese Lacquerware Artisan 50 Kyats Myanmar Authentic Banknote Money for Jewelry and Collage

Obverse: Mythical animal Chinthe/Chinze (lion)

Chinze or Chinthe is a stylized leogryph (lion-like figure) depicted in Burmese iconography and Myanmar architecture, especially used as pair of guardians flanking the entrances of Buddhist pagodas and kyaung (or Buddhist monasteries). Nowadays, it's one of the most recognizable symbol of Myanmar.

Lettering: မြန်မာနိုင်ငံတော်ဗဟိုဘဏ်

၅၀

50

ငါးဆယ်ကျပ်

Translation: Central Bank of Myanmar

50

50

Fifty Kyats

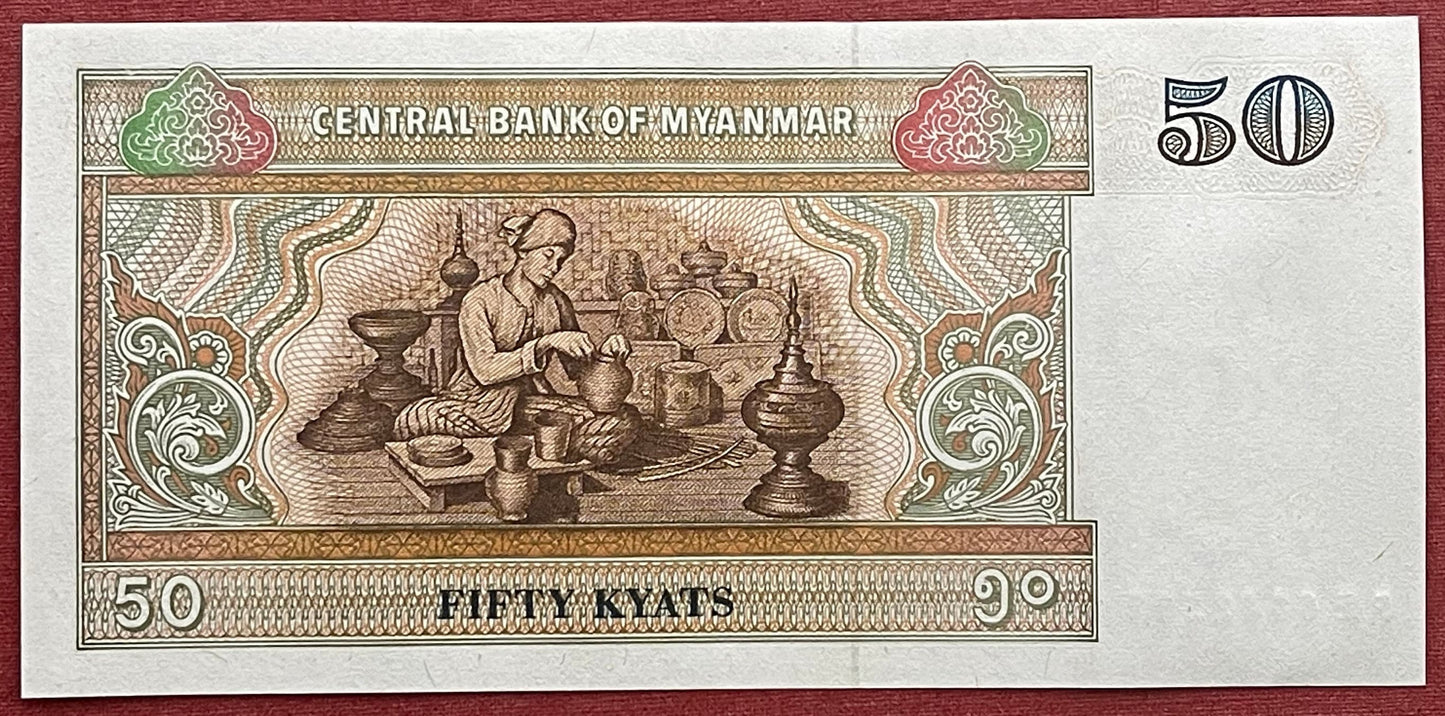

Reverse: Lacquerware artisan

In Myanmar, the lacquering tecnique was introduced during the Fifth Century. The lacquered artifacts of Myanmar usually take on a red, green and yellow color that stands out from the black background, and have golden decorations. The subjects traditionally depicted are court scenes, the tales of Jātaka and the signs of the Burmese zodiac.

Lettering: CENTRAL BANK OF MYANMAR | 50

50 | FIFTY KYATS

Watermark: Chinthe

Features

Issuer Myanmar

Period Union of Myanmar (1988-2011)

Type Standard banknote

Years 1994-1997

Value 50 Kyats

50 MMK = USD 0.028

Currency Union of Myanmar - Third kyat (1989-date)

Composition Paper

Size 145 × 70 mm

Shape Rectangular

Number N# 204072

References P# 73

Wikipedia:

The chinthe is a highly stylized leogryph (lion-like creature) commonly depicted in Burmese iconography and Myanmar architecture, especially as a pair of guardians flanking the entrances of Buddhist pagodas and kyaung (or Buddhist monasteries). The chinthe is featured prominently on most paper denominations of the Burmese kyat. A related creature, the manussiha, is also commonly depicted in Myanmar. In Burmese, chinthe is synonymous with the Burmese word for "lion."

The chinthe is related to other leogryphs in the Asian region, including the sing (สิงห์) of Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and the simha (සිංහ) of Sri Lanka, where it is featured prominently on the Sri Lankan rupee. It is also related to East Asian leogryphs, such as the guardian lions of China, komainu of Japan, shisa of Okinawa and Snow Lion of Tibet.

The story of why chinthes guard the entrances of pagodas and temples is given as such from the Mahavamsa:

The princess Suppadevi of Vanga Kingdom (Present day Bengal) had a son named Sinhabahu through her marriage to a lion, but later abandoned the lion who then became enraged and set out on a road of terror throughout the lands. The son then went out to slay this terrorizing lion. The son came back home to his mother stating he slew the lion, and then found out that he killed his own father. The son later constructed a statue of the lion as a guardian of a temple to atone for his sin.

The chinthe is symbolically used as an element of Burmese iconography on many revered objects, including the palin, the Burmese royal thrones and Burmese bells. Predating the use of coins for money, brass weights cast in the shape of mythical beasts like the chinthe were commonly used to measure standard quantities of staple items. In the Burmese zodiac, the chinthe (lion) sign is representative of Tuesday-born individuals.

******

Wikipedia:

Burmese lacquerware

Yun-de is lacquerware in Burmese, and the art is called Pan yun (ပန်းယွန်း). The lacquer is the sap tapped from the varnish tree or Thitsee (Gluta usitata, syn. Melanorrhoea usitata) that grows wild in the forests of Myanmar (formerly Burma). It is straw-colored but turns black on exposure to air. When brushed in or coated on, it forms a hard glossy smooth surface resistant to a degree from the effects of exposure to moisture or heat.

History

Bayinnaung's conquest and subjugation in 1555–1562 of Manipur, Bhamo, Zinme (Chiang Mai), Linzin (Lan Xang), and up the Taping and Shweli rivers in the direction of Yunnan brought back large numbers of skilled craftsmen into Burma. It is thought that the finer sort of Burmese lacquerware, called Yun, was introduced during this period by imported artisans belonging to the Yun or Laos Shan tribes of the Chiang Mai region.

Manufacture and design

Lacquer vessels, boxes and trays have a coiled or woven bamboo-strip base often mixed with horsehair. The thitsee may be mixed with ashes or sawdust to form a putty-like substance called thayo which can be sculpted. The object is coated layer upon layer with thitsee and thayo to make a smooth surface, polished and engraved with intricate designs, commonly using red, green and yellow colors on a red or black background. Shwezawa is a distinctive form in its use of gold leaf to fill in the designs on a black background.

Palace scenes, scenes from the Jataka tales, and the signs of the Burmese Zodiac are popular designs and some vessels may be encrusted with glass mosaic or semi-precious stones in gold relief. The objects are all handmade and the designs and engraving done free-hand. It may take three to four months to finish a small vessel but perhaps over a year for a larger piece. The finished product is a result of teamwork and not crafted by a single person.

Forms

The most distinctive vessel is probably a rice bowl on a stem with a spired lid for monks called hsun ok. Lahpet ok is a shallow dish with a lid and has a number of compartments for serving lahpet (pickled tea) with its various accompaniments. Stackable tiffin carriers fastened with a single handle or hsun gyaink are usually plain red or black. Daunglan are low tables for meals and may be simple broad based or have three curved feet in animal or floral designs with a lid. Water carafes or yeidagaung with a cup doubling as a lid, and vases are also among lacquerware still in use in many monasteries.

Various round boxes with lids, small and large, are known as yun-it including ones for paan called kun-it (Burmese: ကွမ်းအစ်; betel boxes). Yun titta are rectangular boxes for storing various articles including peisa or palm leaf manuscripts when they are called sadaik titta. Pedestal dishes or small trays with a stem with or without a lid are known as kalat for serving delicacies or offering flowers to royalty or the Buddha. Theatrical troupes and musicians have their lacquerware in costumes, masks, head-dresses, and musical instruments, some of them stored and carried in lacquer trunks. Boxes in the shape of a pumpkin or a bird such as the owl, which is believed to bring luck, or the hintha (Brahminy duck) are common too. Screens and small polygonal tables are also made for the tourist trade today.

Industry

Bagan is the major centre for the lacquerware industry where the handicraft has been established for nearly two centuries, and still practiced in the traditional manner. Here a government school of lacquerware was founded in the 1920s. Since plastics, porcelain and metal have superseded lacquer in most everyday utensils, it is today manufactured in large workshops mainly for tourists who come to see the ancient temples of Bagan. At the village of Kyaukka near Monywa in the Chindwin valley, however, sturdy lacquer utensils are still produced for everyday use mainly in plain black.

A decline in the number of visitors combined with the cost of resin, which has seen a 40-fold rise in 15 years, has led to the closure of over two-thirds of more than 200 lacquerware workshops in Bagan.

Share

Great seller who never disappoints. This is the first time I've bought paper money from them, and like the coins, it is in excellent condition. Thank you!

Beautiful. Definitely coming back for more.

Beautiful bill! So glad this is a part of my collection now. Will be buying from here again!