elemintalshop

Activist Concepción Ramírez with Xk'op Tocoyal Headdress 25 Centavos Guatemala Authentic Coin Money for Jewelry (Choca) (Atitlan) (Maya)

Activist Concepción Ramírez with Xk'op Tocoyal Headdress 25 Centavos Guatemala Authentic Coin Money for Jewelry (Choca) (Atitlan) (Maya)

Couldn't load pickup availability

Human Rights Activist Concepción Ramírez wearing Xk'op Tocoyal Headdress 25 Centavos Guatemala Authentic Coin Money for Jewelry and Craft Making (Choca) (Santiago de Atitlan) (Tzutujil Maya) (Dona Chonita)

Reverse: Activist Concepción Ramírez (AKA "Dona Chonita") wearing a xk'op (tocoyal) head-dress made of fabric wound around the head twenty times.

Lettering: 25 CENTAVOS

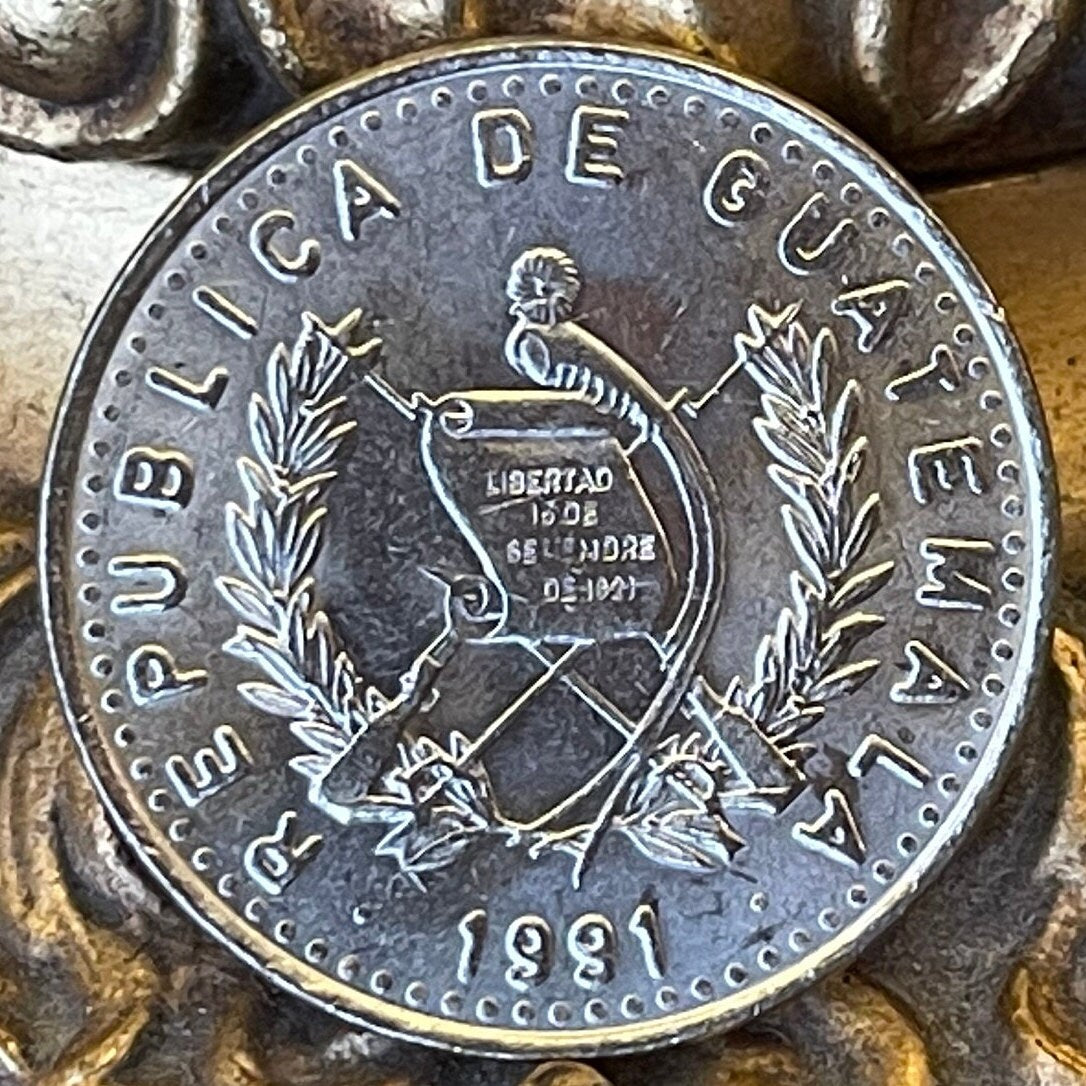

Obverse: The country name above the Guatemalan coat of arms (two laurel branches around a quetzal bird perched on a scroll and the phrase "Libertad 15 De Setiembre De 1821" written on the scroll along with two rifles and two swords crossed behind the scroll).

Translation: Republic of Guatemala

Liberty 15th of September 1821

Edge: Smooth with incised lettering: REPUBLICA DE GUATEMALA C.A.

Translation: Republic of Guatemala Central America

Features

Issuer Guatemala

Period Republic (1841-date)

Type Standard circulation coin

Years 1977-2000

Value 25 Centavos

0.25 GTQ = USD 0.032

Currency Quetzal (1925-date)

Composition Nickel brass (61% Copper, 20% Zinc, 19% Nickel)

Weight 8 g

Diameter 27 mm

Thickness 1.96 mm

Shape Round

Technique Milled

Orientation Coin alignment ↑↓

Number N# 2437

References KM# 278, Schön# 57

Wikipedia:

María de la Concepción Ramírez Mendoza (8 March 1942 – 10 September 2021) was a peace activist from Guatemala and whose portrait appears on the Guatemalan 25 centavo coin, known as the choca.

Biography

Ramírez was born on 8 March 1942 in Santiago Atitlán, a town in the department of Sololá. Her father was an evangelical preacher and her mother taught her traditional crafts at home. In 1965 she married Miguel Ángel Reanda Sicay and they went on to have six children.

In 1959, at the age of 17, her portrait was chosen to feature on the 25-centavo coin as a result of a competition to find the 'prettiest indigenous woman' in Guatemala. The portrait was prepared from photographs by the artist Alfredo Gálvez Suárez. People refer to her portrait as the "woman of the choca" and is recognised by people across the country.

The coin's design features Ramírez wearing a tocoyal head-dress, which is shaped like Lake Atitlán, and made of fabric wound around the head twenty times.

Guatemala has a violent political past and her family was affected by it: on 7 January 1980, her father was tortured to death with 27 other people; on 22 May 1990 her husband was murdered with three other people in a wave of political violence. In reaction to this, Ramírez spoke out against political violence and in 2007 she had the honour of laying a white rose, in Palm of Peace at the National Palace of Culture, and in the delivery of a document related to the internal armed conflict.

Ramírez became a spokesperson for Tz'utujil culture and was passionate about keeping its traditions and language alive. In 2019, the park in Santiago Atitlán was remodeled to include a monument to her shaped like a one meter choco coin.

Awards: Municipal Order of the Tzutujil Kingdom (2019)

*****

The Woman on the 25 Cent Coin and Other Voices of Genocide

PHOTO: CONCEPCIÓN RAMÍREZ, THE WOMAN ON THE 25-CENT COIN.

BY NATALI KEPES CÁRDENAS – FOUNDER AND DIRECTOR, REACH

On the 25-cent coin is the face of Concepción Ramírez, from the Maya Tz'utujil people of Santiago Atitlán. She was paid two quetzales to become the “symbolic indigenous” of Guatemala, the only indigenous person in the currency of a country where more than 40 percent is indigenous.

They murdered her father and husband during the armed conflict, in which 200,000 people died, more than a million were displaced, and countless witnesses who were raped, tortured, widowed, orphaned, traumatized and dispossessed of their land and possessions.

The town of Ramírez suffered one of the last massacres of the conflict. Here is his testimony, translated from the Maya Tz'utujil. It is part of a REACH (Research-Education-Action-Change) campaign to collect testimonies from survivors of the Guatemalan genocide to better understand the consequences that still linger and the views of survivors on what kind of support they need now to overcome them. This campaign and its findings are discussed below.

Interview excerpt – Concepción Mendoza Ramírez

I am the eldest daughter, my father was a pastor, a great person. When I was 17 years old, my dad was making a drinking water connection when he found out that some people were looking for a person's profile to pose for a 25-cent token and he came to tell me to go with him. That day several of us arrived but I was the one chosen by the president who was elected in 1963-1966, Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes.

Back then it was quiet. We had light and electricity in the town. Human light and electricity. When the military came, they all locked themselves in their houses. They tortured people for money, they tortured people. The first victim was my father, who was a pastor. He was tortured in Chacayá. They took him hostage and shot him. They said that he was a guerrilla leader. His body was found in Agua Escondida.

They killed my husband, Miguel Ángel Mendoza. They tortured him along with two other people, Juan Pablo and Gregorio. The day my husband was killed, I was having a cake when they came to tell me. I ran downstairs to see what had happened. When I saw his body, I couldn't see his face, because he was all tortured. I only remember that I fainted. He was a hard-working, merchant man. According to what people said, they murdered him because when he was on the bus, they took him off the bus and he started shouting why they were doing it and that he was just trying to go to work.

The soldiers returned to threaten us and tell us not to cry and not to say anything else because if we didn't, the same thing would happen to us. They didn't let me cry for my husband. I had to swallow my tears and my pain. I did not know what to do. I did not have money. There was a lot of poverty. I didn't have a studio and I went from house to house asking for odd jobs. I couldn't give my children an education, which was a disgrace in the family. There were many repercussions.

They told us that if we heard the bells ring, something bad had happened and that is why many responded to the call when the bells rang the night of the massacre. Others like me, we lock ourselves up. The next day we found out what had happened. That morning was very hard. It was like it was the end of the world. There was nothing that could comfort us. The sun was not seen. It was a day of mourning. The whole town got up after that night. We all signed a document asking for the military to be removed. We gave photos of the murdered, kidnapped and disappeared people. When we found out that the soldiers had left, we felt very calm, but in the end I am still afraid.

https://www.entremundos.org/revista/cultura/la-mujer-en-la-moneda-de-25-centavos-y-otras-voces-del-genocidio-de-guatemala/

*******

Wikipedia:

The current coat of arms of Guatemala was adopted after the 1871 Liberal Revolution [es] by a decree of president Miguel García Granados. It consists of multiple symbols representing liberty and sovereignty on a bleu celeste shield. According to government specifications, the coat of arms should be depicted without the shield only when on the flag, but the version lacking the shield is often used counter to these regulations.

History

In 1871, for the 50th anniversary of Guatemala gaining independence, president Miguel García Granados asked the mint to produce a design to commemorate the event. The Swiss engraver Juan Bautista Frener designed the shield, and Granados decided to adopt it as the national coat of arms, abandoning the previous coat of arms which had conservative symbolism. In Executive Decree No. 33 of 18 November, the coat of arms was described:

The arms of the republic will be: a shield with two rifles and two swords crossed with a wreath of laurel on a field of light blue. The middle will harbor a scroll of parchment with the words "Liberty 15 of September of 1821" in gold and in the upper part a Quetzal as the symbol of national independence and autonomy.

The flag and coat of arms were further regulated in detail in a 12 September 1968 decree by the government of president Julio César Méndez Montenegro, specifying the elements, colors, and the specific shade of blue on the shield.

Symbolism

The elements of the coat of arms have the following symbolism:

The Quetzal is the national bird of Guatemala, and represents freedom and independence of the nation.

The crossed Remington rifles are the type used during the 1871 Liberal Revolution, and represent the will to defend Guatemala's interests.

The crossed swords represent justice and honor.

The laurel wreath represents victory.

The parchment at the center reads "Liberty 15 of September of 1821", the date Guatemala gained independence from Spain.

Share

Coins were great quality. They shipped & arrived quickly. I would order again

Excellent as always! Bought ahead of time for Hanukkah.

5 stars review from Buildabeautifulcity