elemintalshop

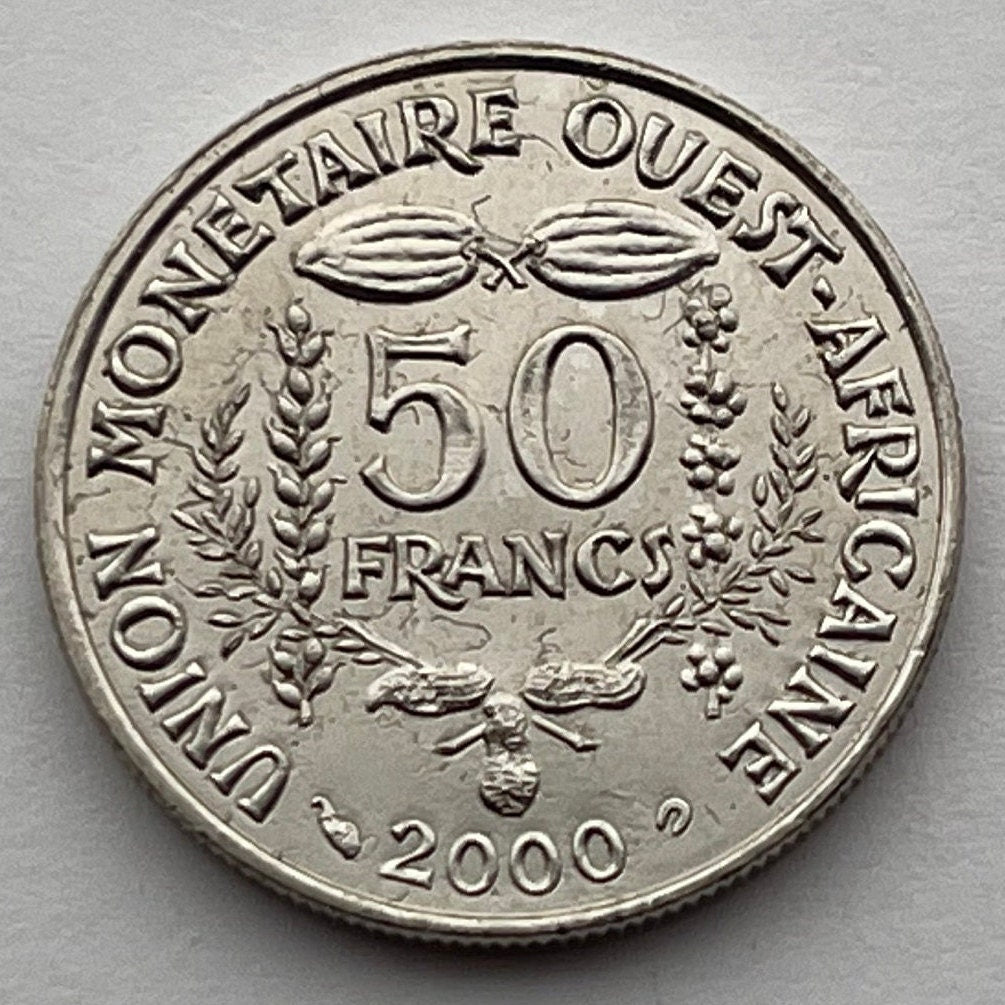

Cocoa Beans, Peanuts & Akan Sawfish Goldweight 50 CFA Francs West African States Authentic Coin Money for Jewelry (Cacao) (Ashanti)

Cocoa Beans, Peanuts & Akan Sawfish Goldweight 50 CFA Francs West African States Authentic Coin Money for Jewelry (Cacao) (Ashanti)

Couldn't load pickup availability

Cocoa Beans, Peanuts & Akan Sawfish Goldweight 50 CFA Francs West African States Authentic Coin Money for Jewelry and Craft Making (Cacao) (Ashanti) (Groundnuts)

Obverse: Emblem of Central Bank of West African States: Akan Goldweight, at center: sawfish-shaped brass weight of the Akan/Ashanti people for weighing gold dust.

Lettering: BANQUE CENTRALE DES ETATS DE L'AFRIQUE DE L'OUEST

Translation: Central Bank of the West African States

Reverse: Denomination within a mixture of cacao beans, peanuts, and grains.

Lettering: UNION MONETAIRE OUEST-AFRICAINE

50 FRANCS

Translation: West African Monetary Union

50 Francs

Edge: Reeded

Features

Location Western African States

Issuing entity Central Bank of Western African States

Type Standard circulation coin

Years 1972-2011

Value 50 Francs CFA

50 XOF = USD 0.08

Currency CFA franc (1958-date)

Composition Copper-nickel

Weight 5 g

Diameter 22 mm

Thickness 1.6 mm

Shape Round

Technique Milled

Orientation Coin alignment ↑↓

Number N# 1798

References KM# 6, Schön# 14

Cocoa production in West Africa, a review and analysis of recent developments

-- Marius Wessela, P.M. Foluke Quist-Wessel

Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1573521415000160

* Seventy percent of the world cocoa production is produced by small holders in West Africa.

* Cocoa production increased by fifty percent in the first decade of the 21st century.

* Yields remained low because of extensive cultivation practices and old age of cocoa farms.

*Large government rehabilitation and replanting schemes are undertaken.

* Implementation of these schemes and higher cocoa producer prices offer scope for higher coca output from West Africa.

* Climatic change and increased land use for food crops will negatively affect the cocoa output in the long run.

* Conditions for sustainable coca production require major structural changes in the entire cocoa sector.

This paper reviews the present condition of cocoa growing in West Africa where some six million ha are planted with cocoa which provide about 70 percent of the total world production. Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana are the largest producers, followed by Nigeria and Cameroon. In the beginning of the 21st century the cocoa production increased from about 2,000,000 tons to about 3,000,000 tons in 2010 and subsequent years. While in this period expansion of the cocoa area (at the expense of forest land) contributed to increased production, nowadays more cocoa has to come from higher yield per ha which is very low at present. This paper highlights at first cocoa growing in each of the cocoa producing countries and then deals with the common constraints and options to higher yields, especially those in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. The major causes of low yield are a high incidence of pests and diseases, the old age of cocoa farms and lack of soil nutrients.

Concerns about declining output due to aging and diseased trees have urged the government of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana to launch large rehabilitation and replanting schemes which provide farmers with improved planting materials, plant protection chemicals and fertilizers. As owners of small farms do not earn enough income from their cocoa to purchase external inputs, the traditional mixed planting of cocoa and forest and fruit trees and some oil palms is discussed as an alternative to a high input approach. This low input low output system is sustainable but not the way forward to higher yields.

It is thought that in the short run higher cocoa prices and improved management including pest and disease control and to a certain extent fertilizer use offer scope for a larger cocoa output. In the more distant future the predicted climatic change and increased land use for food production will reduce the size of the cocoa area and affect the leading position of West Africa on the world cocoa market. This review shows that at present the conditions for sustainable production are not met and concludes that important structural changes in the cocoa sector are needed to reach this goal. These changes concern the economic viability of cocoa on small farms, extensive land use and the ecological impact of the current cocoa growing practice. The implementation of these changes requires area specific programs with as their common goal increased economic and environmentally sustainable cocoa production on less land.

******

NUTS ABOUT GROUNDNUTS

Posted on February 28, 2016by africanbite

The nutty thing about the groundnut, also known as peanut or groundpea, is that it’s in fact not a nut. Botanically, it is classified as a legume, belonging to the same family as beans, peas and lentils. It is an essential ingredient in cooking across the African continent. There’s the famous groundnut soup of Ghana – a thick soupy sauce based on groundnut and tomato, often served with chicken; the Nigerian suya meat skewers dusted in hot spices mixed with ground peanuts; and there’s spinach or morogo stew cooked with peanut butter in southern Africa.

I’ve seen the first, pale green shoots of the groundnut break through the soil in Senegal; watched as fresh groundnuts have been ground to paste in a traditional stone mill in South Sudan; caught a whiff of the appetizing aroma of groundnuts roasting in metal drums over coal fires in Ghana; and bought recycled glass bottles filled with roasted groundnuts off the street in Cote d’Ivoire and elsewhere in West Africa.

Europeans have really missed something when it comes to the groundnut, eating it mainly only as a salty bar snack. According to Edible: An Illustrated Guide to the World’s Food Plants (National Geographic, 2008), the groundnut is second only to the soybean in protein content, and in much of Asia and Africa it is the crop that yields “the highest protein per acre of any food.” Since it grows underground it is also comparably more resistant to pests such as locusts.

Groundnut paste adds a natural creamy thickness to stews, sauces and smoothies, and gives extra depth and character to cooked vegetables, poultry, meat and fish. When added whole or chopped to a dish, the peanut brings crunch, texture and a rich taste. As a snack in Africa, groundnuts are often served boiled and slightly salted.

The Bambara groundnut (also known as jugo bean) is indigenous to Sub-Saharan Africa, but the peanut is the one widely used in cooking today and commonly referred to as groundnut. It was brought to the continent from South America by the Portuguese colonizers.

“While Africans did use groundnuts of some sort, most notably the Bambara groundnut, prior to the Columbian Exchange, the nut of preference is now certainly the peanut. Peanuts migrated from Africa to the United States during the period of the Slave Trade, forever confusing many who think that peanuts are of African origin. They are from the New World, but they have certainly taken over the minds and hearts, and stomachs, of much of Africa,” notes Jessica B Harris in her classic The Africa Cookbook: Tastes of a Continent (Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 1998).

You can easily make your own groundnut paste to add to a stew by grinding the dry, fresh groundnuts in a mixer, though these days it is also quite easy to find unsweetened peanut butter in the shops.

Source: https://africanbite.com/2016/02/28/nuts-about-groundnuts/

************

Wikipedia:

Sawfish, also known as carpenter sharks, are a family of rays characterized by a long, narrow, flattened rostrum, or nose extension, lined with sharp transverse teeth, arranged in a way that resembles a saw. They are among the largest fish with some species reaching lengths of about 7–7.6 m (23–25 ft). They are found worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions in coastal marine and brackish estuarine waters, as well as freshwater rivers and lakes.

.....The Akan people of Ghana see sawfish as an authority symbol. There are proverbs with sawfish in the African language Duala. In some other parts of coastal Africa, sawfish are considered extremely dangerous and supernatural, but their powers can be used by humans as their saw retains the powers against disease, bad luck and evil. Among most African groups consumption of meat from sawfish is entirely acceptable, but in a few (in West Africa the Fula, Serer and Wolof people) it is taboo. In the Niger Delta region of southern Nigeria, the saws of sawfish (known as oki in Ijaw and neighbouring languages) are often used in masquerades.

**********

Akan goldweights, (locally known as mrammou), are weights made of brass used as a measuring system by the Akan people of West Africa, particularly for wei and fair-trade arrangements with one another. The status of a man increased significantly if he owned a complete set of weights. Complete small sets of weights were gifts to newly wedded men. This insured that he would be able to enter the merchant trade respectably and successfully.

Beyond their practical application, the weights are miniature representations of West African culture items such as adinkra symbols, plants, animals and people.

Scholars use the weights, and the oral traditions behind the weights, to understand aspects of Akan culture that otherwise may have been lost. The weights represent stories, riddles, and code of conducts that helped guide Akan peoples in the ways they live their lives. Central to Akan culture is the concern for equality and justice; it is rich in oral histories on this subject. Many weights symbolize significant and well-known stories. The weights were part of the Akan's cultural reinforcement, expressing personal behaviour codes, beliefs, and values in a medium that was assembled by many people.

....The naming of the weights is incredibly complex, as a complete list of Akan weights had more than sixty values, and each set had a local name that varied regionally.

Collections of weights

Some estimate that there are 3 million goldweights in existence. ... Many of the largest museums of in the US and Europe have sizable collections of goldweights. The National Museum of Ghana, the Musée des Civilisations de Côte d'Ivoire in Abidjan, Derby Museum and smaller museums in Mali all have collections of weights with a range of dates.

Manufacture of the weights

In the past, each weight was meticulously carved, then cast using the ancient technique of lost wax. As the Akan culture moved away from using gold as the basis of their economy, the weights lost their cultural day-to-day use and some of their significance. Their popularity with tourists has created a market that the locals fill with mass-produced weights. These modern reproductions of the weights have become a tourist favorite. Rather than the simple but artistic facial features of the anthropomorphic weights or the clean, smooth lines of the geomorphic weights, modern weights are unrefined and mass-produced look. The strong oral tradition of the Akan is not included in the creation of the weights; however, this does not seem to lessen their popularity.

The skill involved in casting weights was enormous; as most weights were less than 2½ ounces and their exact mass was meticulously measured. They were a standard of measure to be used in trade, and had to be accurate. The goldsmith, or adwumfo, would make adjustments if the casting weighed too much or too little. Even the most beautiful, figurative weights had limbs and horns removed, or edges filed down until it met the closest weight equivalent. Weights that were not heavy enough would have small lead rings or glass beads attached to bring up the weight to the desired standard. There are far more weights without modifications than not, speaking to the talent of the goldsmiths. Most weights were within 3% of their theoretical value; this variance is similar to those of European nest weights from the same time.

Early weights display bold, but simple, artistic designs. Later weights developed into beautiful works of art with fine details. However, by the 1890s (Late Period) the quality of both design and material was very poor, and the abandonment of the weights quickly followed.

*******

The West African CFA franc (French: franc CFA; Portuguese: franco CFA or simply franc, ISO 4217 code: XOF) is the currency of eight independent states in West Africa: Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo. These eight countries had a combined population of 105.7 million people in 2014, and a combined GDP of US$128.6 billion (as of 2018).

The acronym CFA stands for Communauté Financière Africaine ("African Financial Community"). The currency is issued by the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO; Banque Centrale des États de l'Afrique de l'Ouest), located in Dakar, Senegal, for the members of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA; Union Économique et Monétaire Ouest Africaine). The franc is nominally subdivided into 100 centimes but no centime denominations have been issued.

The Central African CFA franc is of equal value to the West African CFA franc, and is in circulation in several central African states. They are both called the CFA franc.

Share