elemintalshop

Three Zebu & Marianne in Winged Phrygian Cap 2 Francs Madagascar Authentic Coin Money for Jewelry and Craft Making (Omby) 1948

Three Zebu & Marianne in Winged Phrygian Cap 2 Francs Madagascar Authentic Coin Money for Jewelry and Craft Making (Omby) 1948

Couldn't load pickup availability

Three Zebu & Marianne in Winged Phrygian Cap 2 Francs Madagascar Authentic Coin Money for Jewelry and Craft Making (Omby)

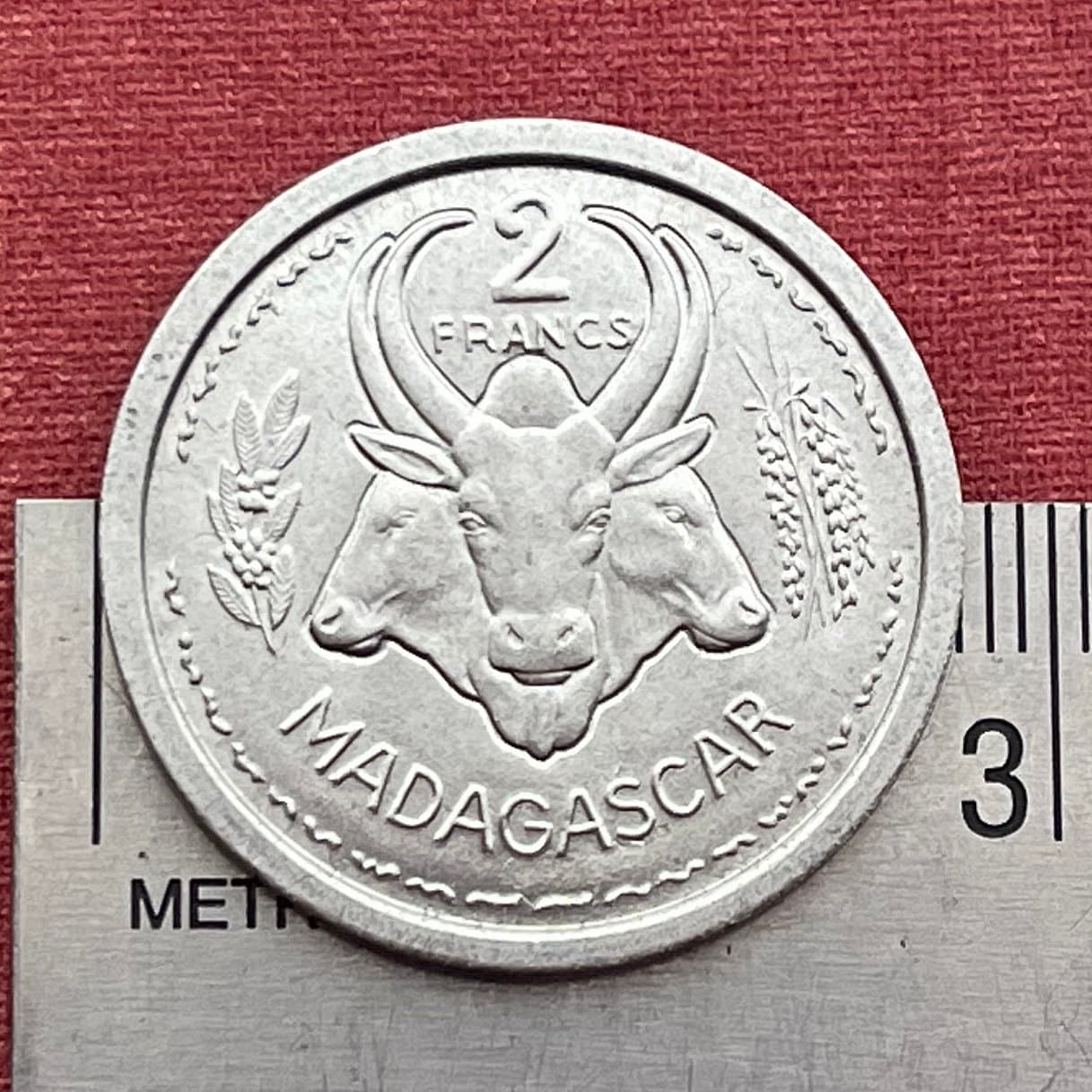

Reverse: Three conjoined zebu heads flanked by sprigs, value within horns.

Lettering: 2 FRANCS

MADAGASCAR

Obverse: Marianne wearing a winged Phrygian cap and four ships in the background. [Probably Port of Toamasina. Wikipedia: "Under French rule, Toamasina ... was the chief port for the capital and the interior. Imports consisted principally of piece-goods, farinaceous foods, and iron and steel goods; main exports were gold dust, raffia, hides, caoutchouc (rubber) and live animals. Communication with Europe was maintained by steamers of the Messageries Maritimes and the Havraise companies, and also with Mauritius, and thence to Sri Lanka, by the British Union-Castle Line."

Lettering: REPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE UNION FRANÇAISE

1948

Translation: French Republic French Union

[N.B. This liberty-themed colonial coin was issued immediately following this anti-colonial uprising, per Wikipedia: "On 29 March 1947, Malagasy nationalists revolted against the French. Although the uprising eventually spread over one-third of the island, the French were able to restore order after reinforcements arrived from France. Casualties among the Malagasy were estimated in the 11,000 to 80,000 range. The repression was accompanied by summary executions, torture, forced regroupings and the burning of villages. The French Army experimented with "psychological warfare": suspects were thrown alive from planes in order to terrorise villagers in the areas of operation."]

Features

Issuer Madagascar

Period French Overseas Territory (1946-1958)

Type Standard circulation coin

Year 1948

Value 2 Francs (2)

Currency CFA franc (1945-1963)

Composition Aluminium

Weight 2.2 g

Diameter 27 mm

Thickness 1.9 mm

Shape Round

Technique Milled

Orientation Coin alignment ↑↓

Demonetized Yes

Number N# 4699

References KM# 4, Lec# 103

From: https://www.evaneos.com/madagascar/holidays/discover/964-1-the-zebu-in-madagascar/

The importance of the omby or zebu in Madagascar

It is a symbol of wisdom, with its big horns and humped back, and an integral part of the landscape of Madagascar. In addition, according to legend, there are as many omby - the Madagascan name for the zebu - as there are people on the island! I hope you found this short explanation of the role of this animal in Madagascan daily life interesting and hope you'll be able to check it out for yourself when you're travelling in Madagascar!

An impressive workforce

As explained in another article, rice is a particularly important grain in Madagascar. Except that without zebus there would be no paddy fields or else there would be a huge amount of work. In fact, zebus are used to tread down the fields before the rice is planted out. When the ground is well and truly waterlogged, the farmers walk up and down the fields with one or two zebus to soften and prepare the soil for planting out the young rice seedlings. This work is much more effective when done by a zebu than by a human being and having tried it myself, I can confirm that!

An ecological means of transport!

The zebu is also used as an ecological means of transport. In a poor country where few people have motorised vehicles and where the price of fuel is unbelievable - about 1 euro per litre - the zebu often replaces the car. Hitched to a little cart and in exchange for a bit of grass, they carry the locals across the winding tracks in the bush, so need for petrol! I have to say that the zebu cart was my favourite means of transport when I went off to explore the bush. You see the landscape at a less frantic pace than in a four-wheel drive vehicle and it will make your trip much more memorable!

A strong cultural importance…

Zebus are also very important in Madagascan culture, where they are a visible sign of wealth. Owning one or - better still- a herd of zebu shows the success and social staus of the owner. In some ethnic groups, a boy only becomes a man when he has stolen his first zebu! Zebus feature in many ceremonies and have an important role in every stage in the life of a Madagascan. From birth to death, they feature in every ritual, even if that means that they are going to take centre stage...

…even after death

For some ethnic groups in southern Madagascar and for the Bara, Antandroy and Mahafaly people in particular, the zebu is actually the object of a cult. When a Mahafaly man dies, his herd of zebus is sacrificed on the day of his burial. The skulls of the animals are then displayed on the deceased's tomb to show his importance and accompany him in the afterlife. The more zebus the better!

During the ceremony, family, friends and the inhabitants of the village are invited to share the meat of the sacrificed zebus at a great celebration. Here, there is no inheritance and children must create their own herd until their death, and so it goes on...

Written by Simon Hoffmann

185 contributions Updated 3 April 2018

https://www.evaneos.com/madagascar/holidays/discover/964-1-the-zebu-in-madagascar/

******

WIkipedia:

Marianne (pronounced [maʁjan]) has been the national personification of the French Republic since the French Revolution, as a personification of liberty, equality, fraternity and reason, and a portrayal of the Goddess of Liberty.

Marianne is displayed in many places in France and holds a place of honour in town halls and law courts. She is depicted in the Triumph of the Republic, a bronze sculpture overlooking the Place de la Nation in Paris, and is represented with another Parisian statue in the Place de la République. Her profile stands out on the official government logo of the country, is engraved on French euro coins, and appears on French postage stamps. It was also featured on the former franc currency. Marianne is one of the most prominent symbols of the French Republic, and is officially used on most government documents.

Marianne is a significant republican symbol; her French monarchist equivalent is often Joan of Arc. As a national icon Marianne represents opposition to monarchy and the championship of freedom and democracy against all forms of oppression. Other national symbols of Republican France include the tricolor flag, the national motto Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité, the national anthem "La Marseillaise", the coat of arms, and the official Great Seal of France. Marianne also wore a Cockade and a red cap that symbolised Liberty.

*********

Wikipedia:

The Phrygian cap (/ˈfrɪdʒ(iː)ən/) or liberty cap is a soft conical cap with the apex bent over, associated in antiquity with several peoples in Eastern Europe and Anatolia, including the Balkans, Dacia and Phrygia, where it originated. In first the American Revolution and then French Revolution, it came to signify freedom and the pursuit of liberty, although Phrygian caps did not originally function as liberty caps. The original cap of liberty was the Roman pileus, the felt cap of manumitted (emancipated) slaves of ancient Rome, which was an attribute of Libertas, the Roman goddess of liberty. In the 16th century, the Roman iconography of liberty was revived in emblem books and numismatic handbooks where the figure of Libertas is usually depicted with a pileus. The most extensive use of a headgear as a symbol of freedom in the first two centuries after the revival of the Roman iconography was made in the Netherlands, where the cap of liberty was adopted in the form of a contemporary hat. In the 18th century, the traditional liberty cap was widely used in English prints, and from 1789 also in French prints; by the early 1790s, it was regularly used in the Phrygian form.

It is used in the coat of arms of certain republics or of republican state institutions in the place where otherwise a crown would be used (in the heraldry of monarchies). It thus came to be identified as a symbol of republican government. A number of national personifications, in particular France's Marianne, are commonly depicted wearing the Phrygian cap.

*******

Wikipedia:

Background and French protectorate

The United Kingdom had been an ally of Madagascar. In May 1862, John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, Britain's foreign secretary instructed Connolly Pakenham that Radama II should keep the country away from foreign powers. In 1882, the French started to occupy much of Madagascar's northern and western territories. In 1883, the Franco-Hova Wars commenced between France and Merina Kingdom, the war remained inconclusive. The British government acted as a restraining hand on France's desire to swallow up the island. On 17 December 1885, Queen Ranavalona III signed the treaty in which Madagascar became a French protectorate and with huge amount of 10 million francs. In 1888, the queen was granted the Grand-Croix of the Légion d'Honneur. The queen was reluctantly passionate about preventing her country to fall to France. The queen tried to cease French incursion, however remained futile and in September 1895, the queen was forced to surrender Madagascar's capital, Tananarive to the French.

According to the queen's perspective, the treaty was supposed to preserve her crown and the monarchy in Madagascar, however France's yearning for expanding their colonial empire in Africa, the treaty proved to be nothing, but a ruse. Queen Ranavalona was removed from power and was exiled to French island of Réunion for two years, following by moving to Algiers after. After her exile, Madagascar formally became a French colony.

Madagascar as French colony

The pacification led by the French administration lasted about fifteen years, in response to the rural guerrillas scattered throughout the country. In total, the repression of this resistance to colonial conquest claimed more than 100,000 Malagasy victims.

Nationalist sentiment against French colonial rule emerged among a group of Merina intellectuals. The group, based in Antananarivo, was led by a Malagasy Protestant clergyman, Pastor Ravelojoana, who was especially inspired by the Japanese model of modernization. A secret society dedicated to affirming Malagasy cultural identity was formed in 1913, calling itself Iron and Stone Ramification (Vy Vato Sakelika, VVS). Although the VVS was brutally suppressed, its actions eventually led French authorities to provide the Malagasy with their first representative voice in government.

Malagasy veterans of military service in France during the First World War bolstered the embryonic nationalist movement. Throughout the 1920s, the nationalists stressed labour reform and equality of civil and political status for the Malagasy, stopping short of advocating independence. For example, the French League for Madagascar, under the leadership of Anatole France, demanded French citizenship for all Malagasy people in recognition of their country's wartime contribution of soldiers and resources. A number of veterans who remained in France were exposed to French political thought, most notably the anti-colonial and pro-independence platforms of socialist parties. Jean Ralaimongo, for example, returned to Madagascar in 1924 and became embroiled in labour questions that were causing considerable tension throughout the island.

Among the first concessions to Malagasy equality was the formation in 1924 of two economic and financial delegations. One was composed of French settlers, the other of twenty-four Malagasy representatives elected by the Council of Notables in each of twenty-four districts. The two sections never met together, and neither had real decision-making authority. Huge mining and forestry concessions were granted to large companies. Indigenous leaders loyal to the French administration were also granted part of the land. Forced labour was introduced in favour of the French companies.

The 1930s saw the Malagasy anti-colonial movement gain momentum. Malagasy trade unionism began to appear underground and the Communist Party of the Region of Madagascar was formed. But as early as 1939, all organisations were dissolved by the administration of the colony, which opted for the Vichy regime.

Only in the aftermath of the Second World War was France willing to accept a form of Malagasy self-rule under French tutelage. In the autumn of 1945, separate French and Malagasy electoral colleges voted to elect representatives from Madagascar to the Constituent Assembly of the Fourth Republic in Paris. The two delegates chosen by the Malagasy, Joseph Raseta and Joseph Ravoahangy, both campaigned to implement the ideal of the self-determination of peoples affirmed by the Atlantic Charter of 1941 and by the Brazzaville Conference of 1944.

Raseta and Ravoahangy, together with Jacques Rabemananjara, a writer long resident in Paris, organised the Democratic Movement for Malagasy Restoration (MDRM), the foremost among several political parties formed in Madagascar by early 1946. Although Protestant Merina was well represented in MDRM's higher echelons, the party's 300,000 members were drawn from a broad political base reaching across the entire island and crosscutting ethnic and social divisions. Several smaller MDRM rivals included the Party of the Malagasy Disinherited (Parti des Déshérités Malgaches), whose members were mainly côtiers or descendants of slaves from the Central Highlands.

The 1946 constitution of the French Fourth Republic made Madagascar a territoire d'outre-mer (overseas territory) within the French Union. It accorded full citizenship to all Malagasy parallel with that enjoyed by citizens in France. But the assimilationist policy inherent in its framework was incongruent with the MDRM goal of full independence for Madagascar, so Ravoahangy and Raseta abstained from voting. The two delegates also objected to the separate French and Malagasy electoral colleges, even though Madagascar was represented in the French National Assembly. The constitution divided Madagascar administratively into a number of provinces, each of which was to have a locally elected provincial assembly. Not long after, a National Representative Assembly was constituted at Antananarivo. In the first elections for the provincial assemblies, the MDRM won all seats or a majority of seats, except in Mahajanga Province.

Despite these reforms, the political scene in Madagascar remained unstable. Economic and social concerns, including food shortages, black-market scandals, labour conscription, renewed ethnic tensions, and the return of soldiers from France, strained an already volatile situation. Many of the veterans felt they had been less well treated by France than had veterans from metropolitan France; others had been politically radicalised by their wartime experiences. The blend of fear, respect, and emulation on which Franco-Malagasy relations had been based seemed at an end.

Political divisions of French Madagascar, 1948.

On 29 March 1947, Malagasy nationalists revolted against the French. Although the uprising eventually spread over one-third of the island, the French were able to restore order after reinforcements arrived from France. Casualties among the Malagasy were estimated in the 11,000 to 80,000 range. The repression was accompanied by summary executions, torture, forced regroupings and the burning of villages. The French Army experimented with "psychological warfare": suspects were thrown alive from planes in order to terrorise villagers in the areas of operation. The group of leaders responsible for the uprising, which came to be referred to as the Revolt of 1947, never has been identified conclusively. Although the MDRM leadership consistently maintained its innocence, the French outlawed the party. French military courts tried the military leaders of the revolt and executed twenty of them. Other trials produced, by one report, some 5,000 to 6,000 convictions, and penalties ranged from brief imprisonment to death. According to a source, 90,000 Malagasies died during the uprising, which was brutally shut down by the French colonial regime.

In 1956, France's socialist government renewed the French commitment to greater autonomy in Madagascar and other colonial possessions by enacting the Loi Cadre (Enabling Law). The Loi Cadre provided for universal suffrage and was the basis for parliamentary government in each colony. In the case of Madagascar, the law established executive councils to function alongside provincial and national assemblies, and dissolved the separate electoral colleges for the French and Malagasy groups. The provision for universal suffrage had significant implications in Madagascar because of the basic ethno-political split between the Merina and the côtiers, reinforced by the divisions between Protestants and Roman Catholics. Superior armed strength and educational and cultural advantages had given the Merina a dominant influence on the political process during much of the country's history. The Merina were heavily represented in the Malagasy component of the small elite to whom suffrage had been restricted in the earlier years of French rule. Now the côtiers, who outnumbered the Merina, would be a majority.

The end of the 1950s was marked by growing debate over the future of Madagascar's relationship with France. Two major political parties emerged. The newly created Democratic Social Party of Madagascar (Parti Social Démocrate de Madagascar – PSD) favoured self-rule while maintaining close ties with France. The PSD was led by Philibert Tsiranana, a well-educated Tsimihety from the northern coastal region who was one of three Malagasy deputies elected in 1956 to the National Assembly in Paris. The PSD built upon Tsiranana's traditional political stronghold of Mahajanga in northwest Madagascar and rapidly extended its sources of support by absorbing most of the smaller parties that had been organised by the côtiers. In sharp contrast, those advocating complete independence from France came together under the auspices of the Congress Party for the Independence of Madagascar (Antokon'ny Kongresy Fanafahana an'i Madagasikara – AKFM). Primarily based in Antananarivo and Antsiranana, party support centred among the Merina under the leadership of Richard Andriamanjato, himself a Merina and a member of the Protestant clergy. To the consternation of French policymakers, the AKFM platform called for nationalisation of foreign-owned industries, collectivisation of land, the "Malagachisation" of society away from French values and customs (most notably use of the French language), international nonalignment, and exit from the Franc Zone.

Share